ILL-TREATMENT OF BHAGAT SINGH & AZAD

Despite popular requests to make sparing the life of Shahid Bhagat Singh and others a condition in the on-going negotiations between Gandhi and the Viceroy Irwin, the Gandhi–Irwin Pact signed on 5 March 1931 remained silent on the matter, and Gandhi and the Congress under Nehru as President did effectively precious little to save the braves. Revolutionary Sukhdev, who had not pleaded for himself and his colleagues, wrote an open letter to Gandhi in March 1931 after the Gandhi-Irwin Pact:

“Since your compromise (Gandhi-Irwin pact) you have called off your movement and consequently all of your prisoners have been released. But, what about the revolutionary prisoners? Dozens of Ghadar Party prisoners imprisoned since 1915 are still rotting in jails; in spite of having undergone the full terms of their imprisonments, scores of martial law prisoners are still buried in these living tombs, and so are dozens of Babbar Akali prisoners. Deogarh, Kakori, Machhua Bazar and Lahore Conspiracy Case prisoners are amongst those numerous still locked behind bars. More than half a dozen conspiracy trials are going on at Lahore, Delhi, Chittagong, Bombay, Calcutta and elsewhere. Dozens of revolutionaries are absconding and amongst them are many females. More than half a dozen prisoners are actually waiting for their executions. What about all of these people? The three Lahore Conspiracy Case condemned prisoner (Bhagat Singh, Sukhdev, Rajguru), who have luckily come into prominence and who have acquired enormous public sympathy, do not form the bulk of the revolutionary party…”

The above letter had no effect on Gandhi. The British India Viceroy Lord Irwin recorded in his notes dated 19 March 1931:

“While returning Gandhiji asked me if he could talk about the case of Bhagat Singh, because newspapers had come out with the news of his slated hanging on March 24th. It would be a very unfortunate day because on that day the new president of the Congress had to reach Karachi and there would be a lot of hot discussion. I explained to him that I had given a very careful thought to it but I did not find any basis to convince myself to commute the sentence. It appeared he found my reasoning weighty.”

From the above it appears Gandhi was bothered more about the embarrassment that would be faced by the Congress with Bhagat Singh’s hanging than by the hanging itself. The British “justice” system could allow the British mass-murderer of Jallianwala Bagh to get away scot free, and the British could even generously reward him for that brutality; but people like Bhagat Singh who protested against those brutal acts deserved to be hanged; and Gandhi’s abstruse artefact (was it deliberately abstruse to allow for self-serving flexibility!) of “non-violence” was comfortable with such a position! Gandhi wrote in Young India the following after Bhagat Singh’s martyrdom: “This mad worship of Bhagat Singh has done and is doing incalculable harm to the country. Caution has been thrown to the winds, and the deed of murder is being worshipped as if it was worthy of emulation. The result is brigandage and degradation.”

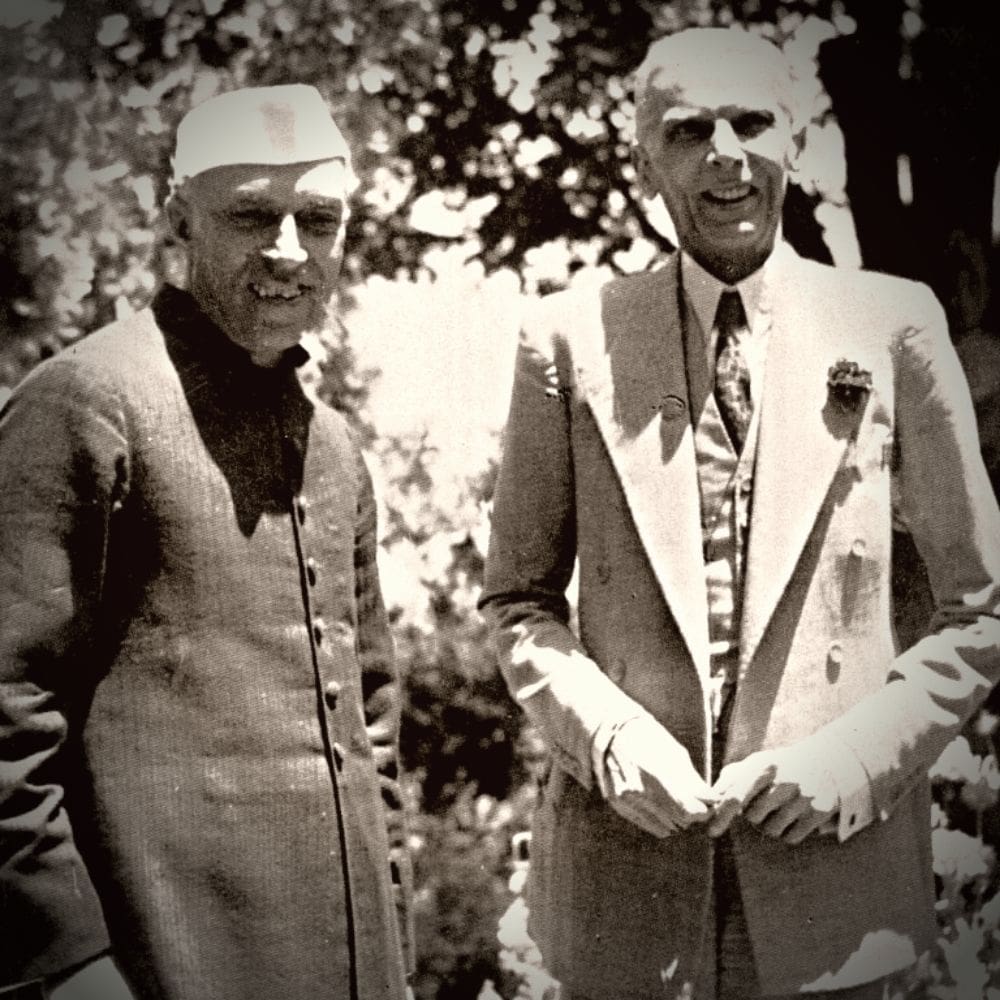

Gandhi used to report back each day’s discussions and agreements with Irwin to the CWC members in the evening; and all agreements were with their concurrence. If Gandhi and the CWC had so desired they could have refused to further proceed with the talks with the Viceroy if he was not agreeable to deal with Shahid Bhagat Singh and colleagues differently. Nehru was the Congress president then, serving his second consecutive term. As Nehru was young then and used to pose as a firebrand leftist- socialist freedom fighter, people had tremendous hope from him that he would leave no stone unturned to save Shahid Bhagat Singh, Rajguru and Sukhdev. But, Nehru did nothing.

Chandrashekhar Azad had met Nehru secretly at Nehru’s residence ‘Anand Bhavan’ at Allahabad in February 1931 to know if Gandhi and the Congress would do something in the ongoing Gandhi-Irwin talks to save Bhagat Singh, Rajguru and Sukhdev from gallows. Rather than doing what Nehru should have, what Nehru wrote about his meeting with Chandrashekhar Azad in his autobiography is not just disappointing, it is disturbing. The casual, disrespectful way he wrote about Chandrashekhar Azad is shocking. Here are some extracts:

“I remember a curious incident about that time, which gave me an insight into the mind of the terrorist group [How he calls them: not freedom fighters, but terrorists!] in India… A stranger came to see me at our house, and I was told that he was Chandrasekhar Azad [even though Azad was famous by then, and there is no way Nehru wouldn’t have known him]… He had been induced to visit me because of the general expectation (owing to our release) that some negotiations between the Government and the Congress were likely. He wanted to know, if, in case of a settlement, his group of people would have any peace. Would they still be considered and treated as outlaws; hunted from one place to place, with a price on their heads, and the prospect of the gallows ever before them? [Would people like Azad plead like this?]…”

Chandrashekhar Azad had shot himself with his last bullet at the Alfred Park in Allahabad on 27 February 1931, after he was surrounded, and had valiantly defended himself and his colleague. An informer had tipped the police. Incidentally, as described above Azad had met Nehru earlier at ‘Anand Bhavan’.